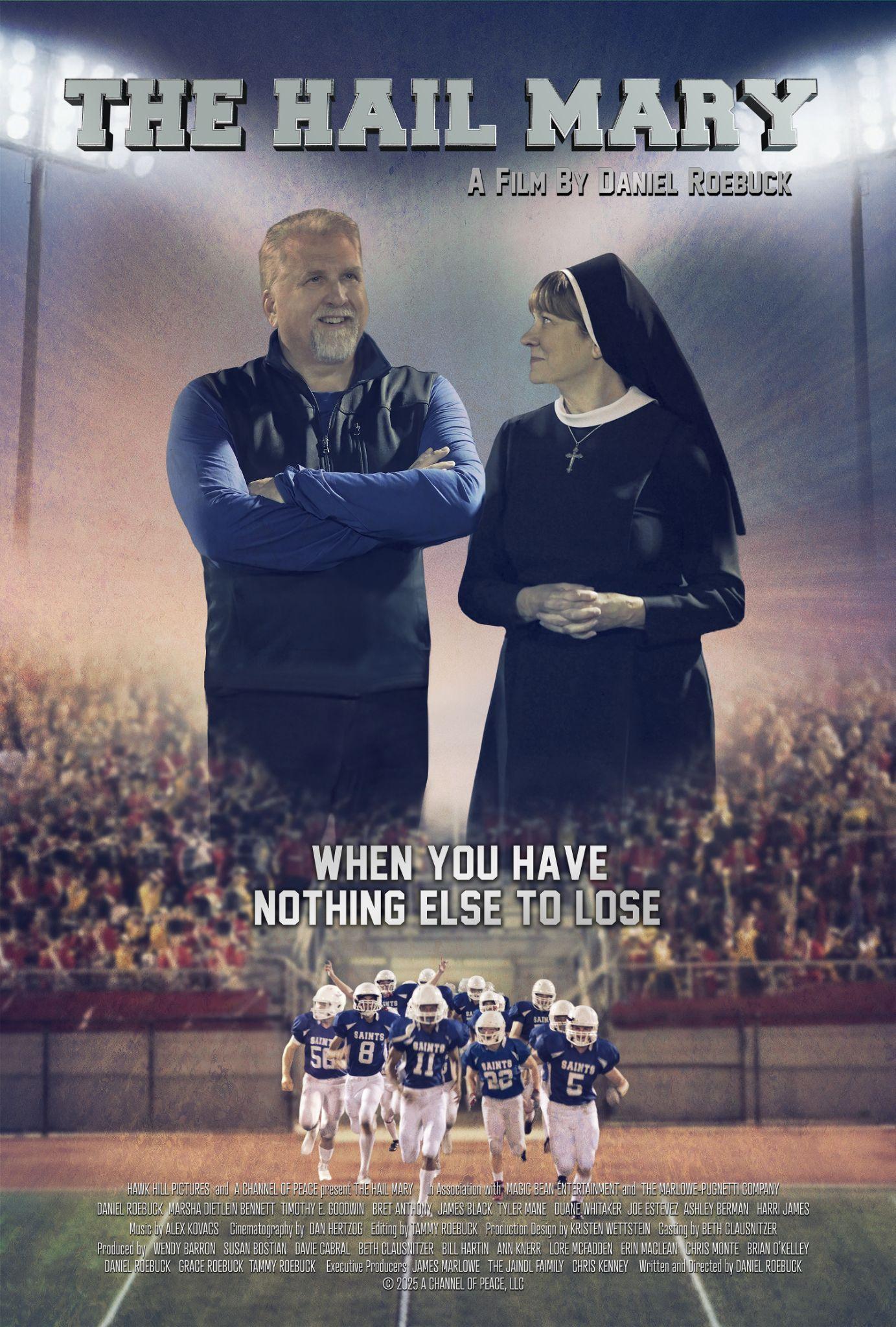

Daniel Roebuck, the veteran actor-filmmaker known for his work in Matlock and The Fugitive, returns with a deeply personal new feature, The Hail Mary, a heartfelt comedy-drama about second chances, faith, and the power of community. Written, directed by, and starring Roebuck, the film follows Jake Bauer, a bitter and isolated man whose life is unexpectedly redirected when he is recruited to coach a struggling Catholic school football team-an assignment that slowly draws him back toward purpose, belonging, and belief through humor, mentorship, and grace that refuses to give up.

Q: How did your own Catholic school upbringing and experiences with religious sisters shape both the story of The Hail Mary and your performance as Jake Bauer?

Well, that is definitely the big question because I don't truly believe I would be in the profession I'm in, successful in the profession I'm in, as happy in the profession as I am, if it wasn't for the guidance and outlook of the Sisters of Saint Joseph of Philadelphia. Now, it's important to know that I have great parents, and my parents get a great deal of credit. I wasn't an orphan. It wasn't like the sisters found me on the doorstep and raised me. They raised me in tandem with my parents, John and Elaine Roebuck from Bethlehem, Pennsylvania.

But the sisters were something-I was never afraid of them because they always appeared to be on our side. I hear so many stories about nuns and rulers and all that nonsense, and I always say, "What did you do?"

Because the sisters that we had were always supportive, and I can look at so many points throughout my life in Catholic school where they didn't turn a blind eye, but they accepted that there were parts of the education-like, say, algebra-that were going to have little impact on my future. I took Algebra, of course, but I remember one time in class I was reading a play and Sister Frances Jerome completely caught me, and as she walked past, she smiled and laughed and kept teaching.

And I've told this before, but I think it's important to note that the story of Sister Kathleen-the reason that they made the nun in the story named Sister Kathy-is because in first grade, this magical Sister Kathleen was everything to me. I walked into school one day with a pile of papers and I presented them to her in first grade at six years old and said, "I wrote a play!"

Now, Sister Kathleen knew something that I didn't know. She knew that I didn't know how to read or write, but that did not deter her from asking about the play, and when she realized that it was a series of drawings-that's how I wrote the play, I just drew the scenes out-she said, "Okay, Daniel, let's do your play." In that moment, she turned me from a thinker to a doer.

Now, this may seem silly, but I want you to think about how important these moments are for a six-year-old kid-when the one person other than your parents who means everything to you believes in you and in whatever nonsense your little brain comes up with. She believed in me, and she taught me how to make my play a reality. We cast some other kids, we rehearsed, and then we performed the play.

I ended up taking my little play to every class in the school-that was two of every grade, sixteen different performances in that day-because that's what the principal wanted me to do when she saw the play. It even seems silly now calling it a play-whatever, it was just a theatrical event a six-year-old empresario dreams up after watching a cartoon.

And then it just gave, through the course of my life, a grand respect for the sisters and the religious, and when it came time to make this movie, naming the main character Kathleen and giving her all of the components that I would think my first-grade teacher would have throughout her life seemed so important. As Sister Kathleen turned little Danny Roebuck from a thinker to a creator, in The Hail Mary, Sister Kathleen gives Jake an opportunity to become who he is truly supposed to be. The parallels are quite striking.

Q: Jake begins the film as a bitter and isolated figure. As an actor, what was most challenging about portraying his resistance to grace and community, and how did you approach his inner transformation?

Well, Jake isn't the most different character for me personally that I've ever played. I mean, I played a teenage killer in River's Edge, and some of the worst people on various versions of CSI and Criminal Minds. But when we're talking about grace, we all have people in our lives who refuse to be touched by it.

And I think it's so strange because, generally, people you meet who are open to or experiencing any kind of relationship with a higher power tend to give up on sweating the small stuff. Because, if you know God has the big stuff, then of course God has the small stuff.

I think a lot of people-those who don't believe-think that's silly. They wonder why God would be concerned about the minutiae of each individual person's life, and it is really kind of looking at the prism backwards. Just as we start as a splitting cell in the moment of conception, meaning we start small and end up pretty big, then of course God would be as concerned about you stubbing your toe as God would be with you driving your car off a cliff. Both those things-one minor and one major-would rip through your day and affect everything and those around you.

So, people like Jake simply refuse to believe, for whatever reason, that God would be concerned about someone as insignificant as them. And that really is the greatest sin of our society: that there's any human being who would consider themselves unworthy of God's love means we all have to do a better job of expressing that everyone is worthy. And in the eyes of Sister Kathleen, she knows better than anybody that everyone is worthy.

So how do you approach that as an actor? Well, I guess the bigger question is how do you approach him as an actor who's also the director, who's also the producer, who's also the writer? I had a clear take on how this movie would be made from the very beginning, so I knew that we had to peel Jake back layer by layer until we got to the real Jake, and I hope we've done that. I hope people are entertained by that.

Q: You chose to frame this redemption story within a Catholic school football program rather than a traditional sports narrative. Why was that setting essential for what you wanted to say about faith and second chances?

You know, I feel very lucky to have been blessed with 12 years of a Catholic education, and there were four of us, so that means all four of us were given 12 years of a Catholic education. I can't even imagine what that cost my middle-class family, but I also educated my children in the exact same manner because I know that a religious education-Catholic or any Christ-centered religion-would give anyone lucky enough to be taught in that manner by righteous people.

What I like most about putting the redemption story at the school and including football is because-and you can hear nothing in my script is a mistake-Sister Kathleen earlier in the movie actually says, "Some men without purpose are as lost as these boys."

Now, there's still a lot to learn about the boys in the story, so you don't know about them, nor at that point in the story do you really know about Jake. That's kind of the joy of a good movie-and hopefully this is a good movie or a great movie-is that you're informed of the story as it goes along; you should never be able to guess what's coming next.

But I love the idea that here we have Jake, who's the adult in the situation, and he is as lost as the boys are, and it takes one of the boys to humble him in that fact. Once it seems like the kids have the upper hand over him, it's the spark that lights the fuse that leads him toward redemption.

But he would've never found that if it wasn't for the direct intervention of Sister Kathleen and her ingenious plan to win his soul back.

Q: As both director and lead actor, how did wearing both hats influence the way you shaped scenes-especially the quieter moments of healing, humor, and reflection?

Every director says 80% or 90% of their job is casting. I get a lot of credit for the excellent work actors do when, in reality, I'm just living on the coattails of these great actors.

Marsha Dietlein Bennett has starred in a few movies that I have made. If I do have a muse, it is her. I think she can do anything. I think she's one of the greatest actresses I have ever seen or worked with, and when we work together, something magical happens.

The same is true of the other actors, Tim Goodwin and Bret Anthony, the Franciscan brothers, as well as some of the supporting cast, who are all familiar faces. I write the roles for them, and it just makes the movie better.

I spend a lot of time thinking about these movies before I actually put pen to paper-or whatever we do now; I guess we don't really put pen to paper-before I type it into the computer. I've worked out dialogue, plot, twists, everything long before I write it.

In this movie, there are a couple of scenes we simply didn't have time for, and I was heartbroken that we had to drop them, but you want to really stay on story when you're telling a story. A lot of independent movies forget that and they meander. I don't like a story that meanders.

I did use a technique stolen from great directors like Sidney Lumet and Milos Forman. For a pivotal bar scene in the third act, we set up two cameras to shoot the characters simultaneously. With an actress as wonderful as Marsha, either one of us could change the scene because we're actors who listen.

One of my favorite techniques-and only an actor who is directing can do this-is if I want something a little different, I actually change my own delivery, which causes the actor who's listening to change their delivery.

I also change stuff on the spot all the time. I shorten it, I lengthen it, I come up with a different joke, they come up with a different joke. It's exciting working with great actors and knowing you're always going to get great stuff.

Q: The film balances comedy with faith and emotional vulnerability. How intentional were you about using humor as a bridge into deeper conversations about forgiveness and mentorship?

Thank you so much for asking this question. I was extremely intentional.

Since we started our non-profit, A Channel of Peace (people can find it at www.channelofpeace.org), my theory has always been that I don't want to preach to the choir. I want to preach to the people driving past the church on Sunday.

If we don't make people laugh, we can't make them love. We have to meet the audience where they are. I want non-believers-people who are anti-church-to laugh all the way through the movie and then stop and think, "What is it that made that guy change?" And the answer is: a relationship with God.

If a character starts out perfect, with no arc, who's going to watch that movie?

God made me funny. I don't know why He chose me, but He did. The jokes don't come when I start writing-they come in the process.

One of the biggest laughs we get-when Tim Goodwin's character says "Hugs or kisses?"-wasn't in the script. I heard it in my ear walking to set and knew it had to be there. I truly believe that was divine inspiration.

Q: You've described The Hail Mary as a story about grace that doesn't give up. What do you most hope audiences-particularly those who may feel distant from faith-take with them after watching the film?

It's my prayer and my greatest hope that anyone who feels excluded from the love of God can find their way back. We are always the lost lambs, and He is always the Shepherd.

Some of us get lost not because He doesn't love us, but because we think we don't need Him.

In today's world, through social media, everyone becomes their own god. People get lost in politics, pornography, and all kinds of rabbit holes. I want audiences to leave knowing that no matter how far they've fallen, there is a God who loves them and a church that should support them.

I used to laugh when actors said they thought their movie could change the world. Now I believe if a movie changes one person, that person might change another. And if that creates a chain reaction of faith, love, and care for one another-then bring it on.